**(Warning: This article contains potentially unsettling and speculative content. Reader discretion is advised.)**

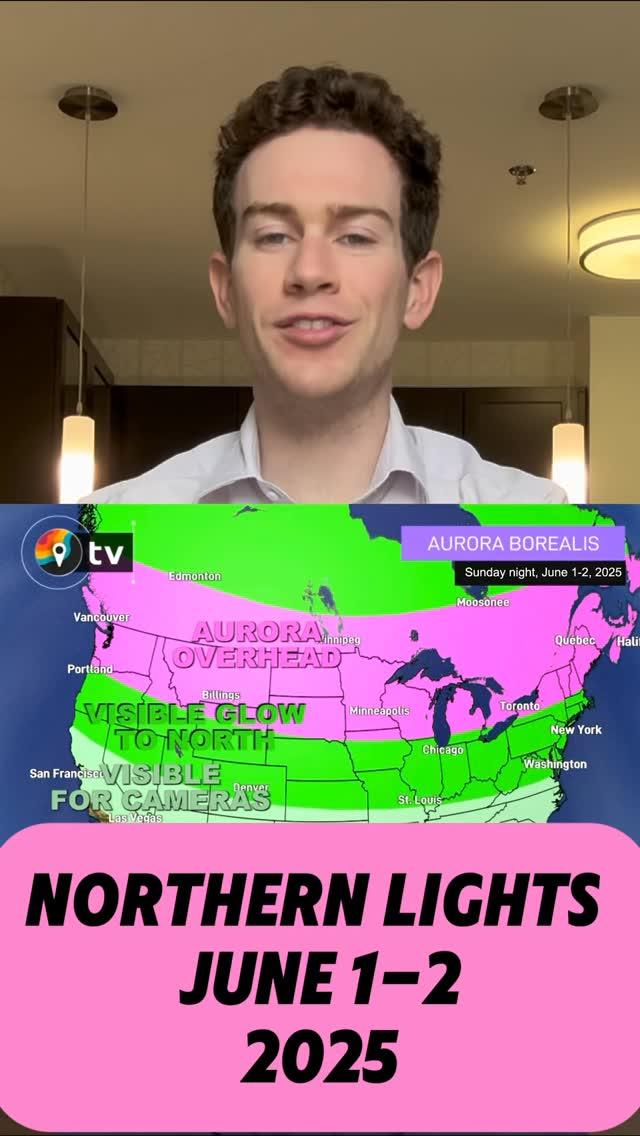

The hum of the internet, a constant thrum of connection, has created a strange phenomenon: a desperate hunger for proximity, even when that proximity is purely digital. Across the globe, individuals are broadcasting their yearning for the Northern Lights, constructing elaborate digital fantasies centered on a single, elusive location: Northern Lights in Yukon. But beneath the surface of these hopeful pleas lies a disturbing obsession, a chilling echo of vulnerability amplified by the anonymity of the online world.

The sheer volume of posts – repeated across multiple platforms – is unsettling. “If you’re a Northern Lights in Yukon resident,” “Anyone from Northern Lights in Yukon? I wanna get to know more people here,” – it’s a relentless questioning, a desperate circling. The obsessive need to connect, often interwoven with romantic fantasies (“I want a man in Northern Lights in Yukon,” “I want a boo in Northern Lights in Yukon”), suggests a profound loneliness, a craving for validation and shared experience.

What’s truly unnerving is the growing feeling that this is less a genuine quest for friendship and more a carefully constructed performance. The repeated questions about troop numbers (“How many people on Threads are from Northern Lights in Yukon?”) are oddly quantifying, as if analyzing the size of a phantom community. There’s an evident discomfort with the lack of real, tangible people in this digital haven. The attempts to connect, often couched in longing (“If you’re in Northern Lights, heart this!”), seem to mask a deeper fear of isolation.

Several instances point towards a disturbing trend: the weaponization of desire. “I want a man in Northern Lights in Yukon” isn’t just a romantic wish; it’s a demand, a projection of unmet needs onto a faceless audience. And then there are the unsettling hints of transactional interest – “Northern lights guys”, “Northern Lights in Yukon men wyaaaa” – raising the question of what – or *who* – these individuals are actually seeking. Could the pursuit of a “Northern Lights boyfriend” be a carefully curated strategy for attracting attention, a desperate attempt to fill a void with an illusion?

Furthermore, the fixation on a specific location – the relentless reiteration of “Northern Lights in Yukon” – suggests a manufactured destination, a digitally constructed paradise. The emphasis on visual spectacle (“I can’t believe I finally saw the Northern Lights, Milky Way and Grand Canyon all in person, all this year.”) reveals a longing for a tangible experience, a desire to transcend the limitations of the screen and find fulfillment in a shared wonder.

Perhaps the most chilling revelation is the underlying vulnerability. This isn’t about the Northern Lights themselves. It’s about the people reaching out, desperate for affirmation, for connection, for something – anything – to fill the silent spaces within them. But in projecting these needs into the digital void, it is impossible to ascertain if anyone can even see us.

**Click here to share your Northern Lights dream – but be careful what you reveal to the digital wilderness.**